Interviews and Webinars : Lou's Views

From World War II to Ukraine today, reporting war is hell

As Russia continues its unjust, horrific war against Ukraine —“special military operation” being a term straight from the Adolph Hitler Nazi Ministry of Misinformation — it’s impossible to overlook the damage on the ground, the slaughter of the innocents, the uncommon courage of everyday people.

By “courage,” we must single out the Ukrainians who’ve taken up arms to defend their homeland from an unjust, brutal conflict sure go down infamy faster that you can say “Dictator Putin.” Among the courageous others, I want to single out the incredible journalists, some of whom have already paid a supreme price for their bravery.

That’s true even at the home of disgraceful Putin apologists such as Tucker Swanson Carlson (he of the frozen-dinner family fame, and arguably more qualified to stuff mystery meat into tin foil trays). On March 14, Fox News lost two contracted Ukrainian journalists near the capital of Kyiv. Oleksandra “Sasha” Kuvshynova, just 24, was working as a consultant for the network. The second, Pierre Zakrzewski, was a 55-year-old longtime war photojournalist.

While this column dedicates a lot of space to writers, editors and TV talking heads, photojournalists don’t get nearly enough love. Their pictures paint countless words; their video footage makes real what we would otherwise write off as the daily body count and words on a press release.

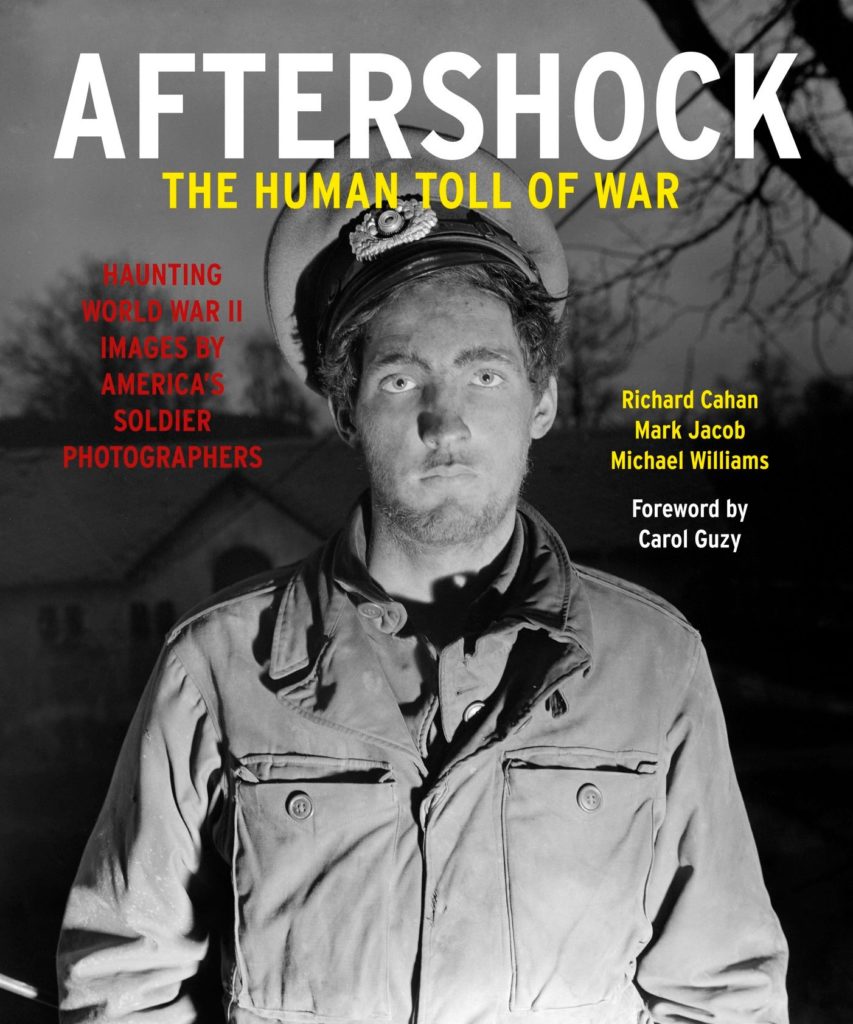

Considering this, I reached out to an intrepid former colleague at the Chicago Tribune. In his distinguished career, Mark Jacob served as foreign/national news editor, editing stories and working through questions and edits over the phone with reporters ensconced in war zones. He’s co-authored a stunning book that puts the spotlight back on the photographers who captured World War II, “Aftermath: The Human Toll of War.” Its contents document a clear line of covering conflict that spans eight decades and many generations to the present day.

A foreign editor brings home war coverage wisdom

In “Aftermath,” Jacob and co-authors Richard Cahan and Michael Williams share images so riveting, I’ve spent hours thumbing through the book again and again. Armed with cameras instead of guns, the soldier photogs of the second world war were commanded to document the worst conflict in our planet’s history. I spoke to Jacob just as the Ukrainian nightmare began to rise up on deathly wings. Here’s what he shared.

Qwoted: How does a deeply interested reader or media hound find the best war coverage? What will be some of the hallmarks to look for?

Jacob: When assessing war coverage, it’s especially important to know how media outlets know something. Do they have reporters and cameras in the field or are they just getting phone calls from unnamed people who may not even be in the war zone? Is there any video to support what they’re saying, and has that video been authenticated? For example, a recent on-camera report from a CNN correspondent in Ukraine showed him standing next to burned-out Russian armored vehicles. That was especially credible because it was a reporter with a track record for accuracy working for a news outlet with a track record for accuracy in war coverage.

Qwoted: What comes with the job of covering this war that will escape the notice of most/all media consumers?

Jacob: I don’t think news consumers have enough understanding of how dangerous it is to leave a secure area and try to find a battle. If a patrol wants to stop the journalist’s vehicle, take them out and shoot them, there’s nothing to stop that from happening. Even the cable news stars standing on Kyiv rooftops are risking their lives by being there. When we see a report from a recent battle scene, we should appreciate that a reporter risked his life to bring the facts to the public.

If a patrol wants to stop the journalist’s vehicle, take them out and shoot them, there’s nothing to stop that from happening.

Another thing news consumers need to understand is that there’s no substitute for being there. When I was on the Chicago Tribune’s war desk in Chicago during the first days of the Iraq War in 2003, I saw a TV report in which a British official in London announced that allied forces had taken the town of Umm Qasr. We sent a message to our war correspondents in the field telling them we planned to add that to our story. One of them, Laurie Goering, messaged back: Don’t. I’m a mile from Umm Qasr and there’s still fighting going on. I can see it and hear it myself.

Qwoted: With “Aftershock,” I was amazed just how hard it was to put down the book. The images are riveting. What do you think these soldier photographers taught us about how to cover war?

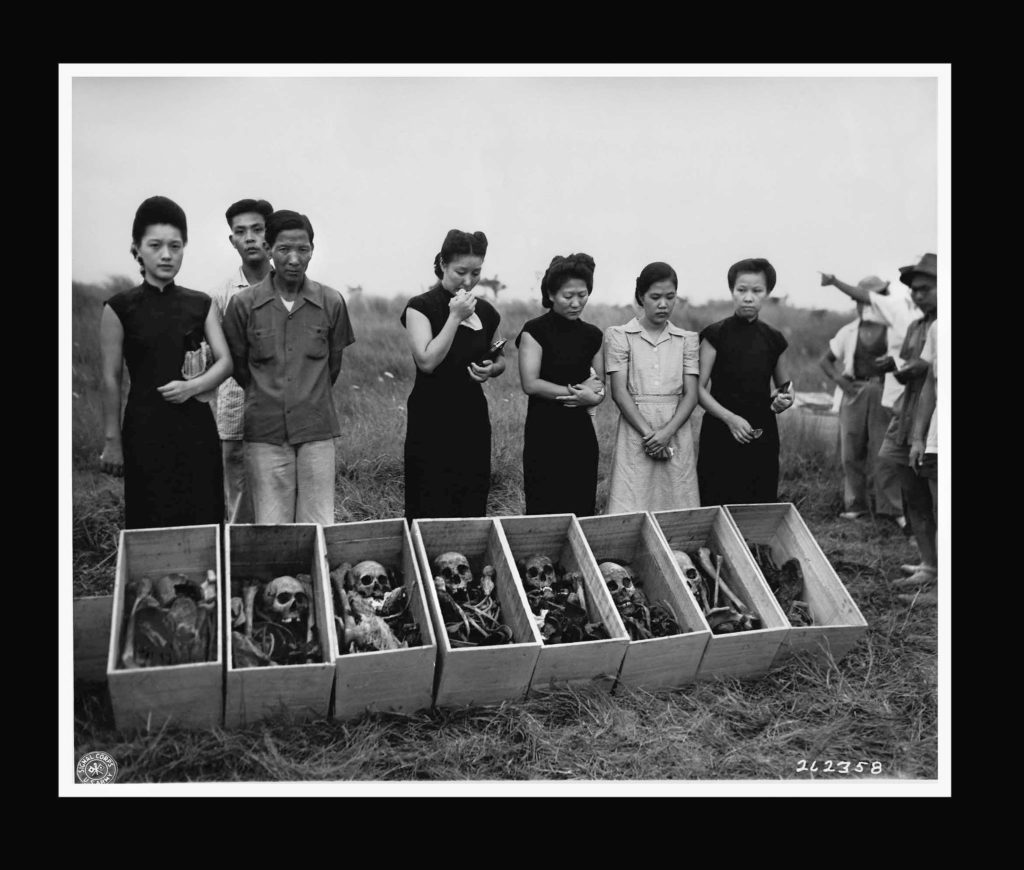

Jacob: The thing that strikes me most about the photos by Army Signal Corps photographers from World War II is the impact of war on civilians. The stunned, desperate looks on their faces. The bodies of civilians after bombings. In the current Russian invasion of Ukraine, we’re seeing how much modern war is total war, with lots of what they call “collateral damage.”

Qwoted: Which media outlets would you say deserve recognition for what they’ve done in Ukraine so far?

Jacob: So far, I’d say CNN and the New York Times are doing especially good jobs covering the Ukraine invasion. You’ll see a careful approach to their reports. When they report claims that they can’t independently verify, they’ll tell you that.

From a not-so-brave Qwoted journalist, a parting shot

I can’t say I long to be in Ukraine; even the sight of blood in a campy horror film freaks me out. Still, this column will hopefully give you some glimpse of the Ukraine situation. Stay tuned as a Yuriy Metsarsky—a Ukrainian journalist now turned soldier—gives us an update on what he’s witnessing, the second in a series of Qwoted updates from his war-torn homeland. You can read and hear his first dispatch by clicking here.

War is hell, and when journalists are taken out by it, we can only hope that their freed souls find heaven. Alive, injured or killed, God bless them all. I’d like to think I could walk even a step in their shoes. I cannot. What they’ve done for generations, and continue to do, serves the calling of the profession in ways few of us will ever realize.

For them, and the people they cover, two words: Slava Ukraini.

Lou Carlozo is Qwoted’s Editor in Chief. All opinions expressed are weak substitutes for brave wartime journalism. Email lou@qwoted.com or connect on LinkedIn.

POPULAR POSTS

LATEST ARTICLES

CATEGORIES